Until some years ago, Finland was one of the more active jurisdictions in Europe for competition damages cases. Since then, there have been none. This does not mean Finnish companies’ risk of being sued or the opportunities to claim damages in these cases have disappeared, they have simply moved abroad.

From about 2010 to 2020, Finland was one of the leading jurisdictions in Europe for competition damages cases, particularly considering its modest size. While large cartel damages cases received the most publicity, cases concerning abuse of dominant position were actually the most common. There were several judgments on the merits, and about a third of the cases were ultimately settled. Yet after this swift start, Finland has completely fallen off the map while elsewhere in Europe competition damages activity has continued to grow rapidly.

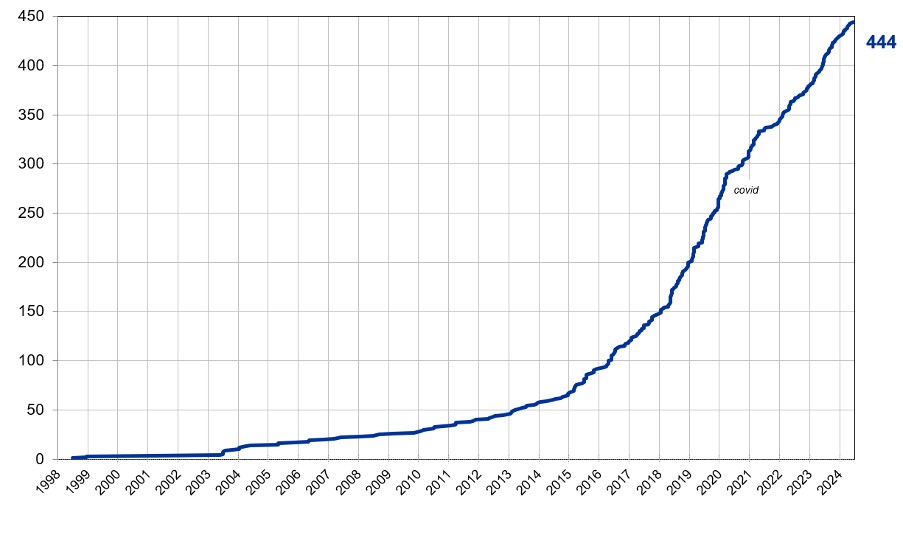

Graph: Cumulative number of European cartel damages cases with judgments

Source: Jean-Francois Laborde, Cartel damages actions in Europe (2025 ed.), Concurrences N. 7-2025

Why is it then that this particular type of cases has disappeared in Finland when it clearly continues to grow elsewhere in Europe? And what does this mean for Finnish companies that could be claimants or defendants in this type of cases? The current situation seems to be due to a combination of factors.

Why competition damages cases left Finland

First, the number of successful public enforcement cases brought by the Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority (FCCA) has been fairly low for several years. This means there are quite few domestic infringement cases that could result in follow-on damages claims. As regards multi-country infringements found by the European Commission, the damages cases stemming from them have in practice been rarely litigated in Finland.

Second, a number of the cases successfully brought by the FCCA have involved a situation where possible price increases caused by the infringement have likely been largely passed downstream in the production and supply chain, ultimately ending up with individual consumers. This limits the possibility and incentives of the infringers’ direct customers to bring claims because they will not be able to recover damages to the extent they mitigated their loss by raising their own prices. Passing on also makes the damages assessment even more complex than usual. At the same time, Finland does not have a functional collective action regime that would allow injured parties to pool their claims when individual claims are too small to be viable. This can lead to a situation where the damages are so pulverized that no one has a sufficient incentive or ability to bring a claim.

Third, the largest early competition damages cases were very expensive to litigate by Finnish standards because of their size, complexity and the number of open legal questions. No one looks forward to long and expensive litigation, particularly if the outcome is quite uncertain. Furthermore, third-party funding is very rarely used in Finland, even though there are no particular legal obstacles to it.

Fourth, the most high-profile cases resulted overall in somewhat defendant-friendly judgments, though the EU’s Competition Damages Directive and new case law from the EU’s Court of Justice have made the situation more claimant-friendly since then. But combined with possibly high litigation costs, this does not present an encouraging situation for potential claimants.

Fifth, certain other jurisdictions, such as the UK and the Netherlands, have become so strongly favoured that cases are being brought from other countries to be litigated there if the claimant is able to choose them as a jurisdiction. These leading jurisdictions tend to have courts or judges that specialize in competition damages cases, have functional opt-out collective actions and third-party funding available. Similar improvements are currently not even being discussed in Finland.

Finnish cases go international

The outcome is that Finnish competition damages cases have not disappeared but are being litigated outside Finland. I know this as I have written expert opinions on the interpretation of Finnish law in such cases. Finnish claimants are joining collective actions abroad and Finnish defendants or their local subsidiaries are being sued abroad as part of these collective proceedings.

Thus, while it looks unlikely that Finland itself will become an active competition damages jurisdiction anytime soon, the risk of ending up as a defendant or the opportunity to claim damages have not disappeared. Indeed, especially for claimants, it is probably more attractive to take part in a foreign collective claim with third-party funding instead of litigating a case by itself because it greatly mitigates the cost risk while still retaining a significant upside if the case is won or settles.

Contact authors