The level of GDPR fines in Finland is still modest in international comparison but has seen a rapid increase. As such, it is important to know there is a risk that GDPR fines could be imposed not only on the infringing company but also its parent company or a company that acquired the infringing company’s assets.

GDPR fines in Finland: A changing landscape

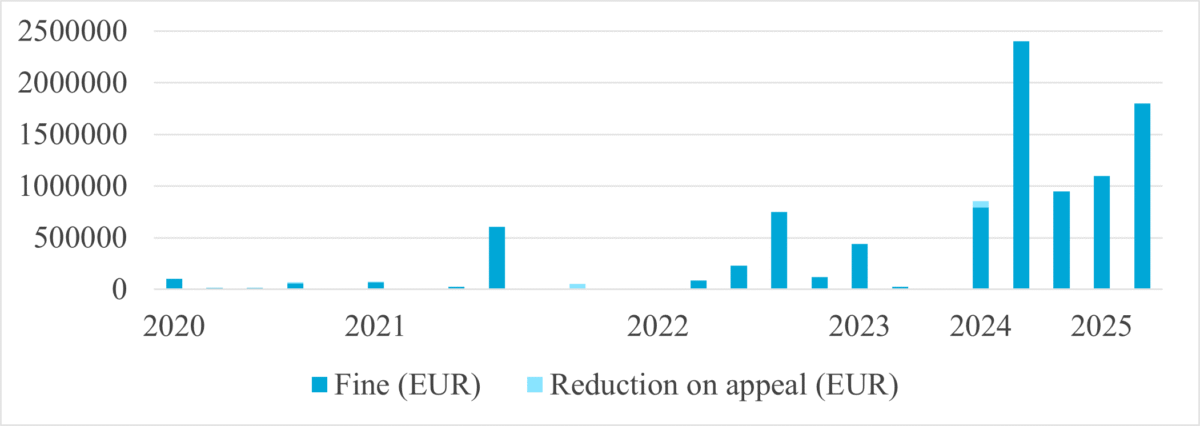

With the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018, the Finnish Data Protection Ombudsman gained vastly enhanced powers to impose fines for data protection infringements. Despite this, for the first several years, fines mostly remained relatively modest in absolute monetary terms. This has clearly changed from 2024 onwards with fines now routinely around EUR 1 million or more, and a trend showing increase over time.

Graph: GDPR fines imposed in Finland

This increased level of fines makes it important to understand in more detail the rules of who exactly can be held liable for the fine.

Direct liability: The basic principle and initial complications

The main rule is simple: the legal person that committed the infringement has to pay the fine. In GDPR terms, this refers to the data controller or data processor that is found guilty of having infringed its obligations under the GDPR. If several different parties have contributed to the infringement, they can be held liable to the extent of their own actions.

Yet this simple main rule hides a more complicated reality. In addition to controllers and processors, the fining provisions in GDPR also mention ‘undertakings’, particularly in the calculation of the maximum amount of a fine. Under GDPR, if the infringer is an undertaking, then the maximum amount of the fine is calculated as a percentage of the global turnover of the undertaking. While the concept of undertaking is not defined in the GDPR, it seems to mean an entity or a group of entities engaged in business activities. Thus, if the infringing legal entity is part of a company group, the maximum amount of the fine can be calculated from the global turnover of the entire company group. The theory behind this is that such a company group is treated as a single economic unit, even though it is composed of separate legal entities. So far, all this is settled law.

Group liability: The undertaking concept and competition law

Certainty ends when the GDPR unexpectedly states that, in the context of fines, undertakings should be understood in accordance with EU competition law.

Where administrative fines are imposed on an undertaking, an undertaking should be understood to be an undertaking in accordance with Articles 101 and 102 TFEU for those purposes. (Recital 150 of the GDPR)

The reference to EU competition law is unclear and its scope is open to interpretation. There are two main possibilities it can refer to. The first one is that under EU competition law, the maximum amount of a fine is calculated from the global turnover of a company group, just like for GDPR fines. The second one is that the liability for fines can be imposed more flexibly to various legal entities within a company group and, in certain circumstances, can also be imposed to the purchaser of the assets of an infringing legal entity.

It is possible that the reference to EU competition law is intended to merely repeat and confirm that the maximum amount of a fine for an undertaking is calculated from the global turnover of the company group. However, that interpretation seems strange because there has been no serious doubt about this interpretation under the GDPR, and it would be unnecessary to refer to EU competition law.

But there is also a clear risk that the reference to EU competition law rules is intended to allow for more flexible targeting of the liability for fines. Under EU competition law, the liability for competition fines can be attributed to different legal entities within a company group in ways that bypass the principle that each legal entity is only liable for its own actions. In special circumstances, the liability can even be imposed on a legal entity that merely acquired the assets of an infringing legal entity without participating in the infringement.

Extended liability risks: Parental liability and economic continuity

The first situation is commonly referred to as parental liability. It means that the fine can be imposed jointly and severally on the parent company in a company group, even if it did not participate in the infringement committed by a subsidiary. The second one concerns the so-called principle of economic continuity where the liability for an infringement is attached to the assets of the infringer and transfers to the acquirer of those assets, even if the acquirer did not participate in the infringement, if the original infringer is unable to pay the fine.

This can lead to nasty surprises in M&A activities because while the purpose of asset deals is typically to agree exactly on the assets and liabilities that are purchased, it is not possible to validly agree to exclude the liabilities transferred via economic continuity.

So far, the Finnish Data Protection Ombudsman’s Office has at times hinted at the possibility to target the fine more flexibly but has not yet done so, possibly because it has not been necessary under the cases that the Ombudsman has dealt with so far. As long as this unclear situation persists, it is prudent to be mindful of these risks, particularly within company groups and in connection to corporate acquisitions.

Contact authors