How to adopt Legal Tech to effectively meet the enhanced compliance expectations in digital transformation?

Compliance. Code of conduct. Ethics. Sustainability. Responsibility. Perhaps never before has the importance of compliance been acknowledged and agreed as crystal clearly as today. Nowadays it is no longer accepted as the minimum threshold that the black letter of law is followed. In addition, one must also do “the right thing”, achieve a higher threshold of compliance, where the operations are on a sustainable basis on all levels, including the digital transformation, even when transparently and objectively addressed from outside. This shift in the expectations goes across different business operations and software development is no exception.

So far, whenever code assets have been discussed, there has been a clear division on the “valuable” proprietary code (which should be protected) as opposed to the “free” open source code, which, at minimum, should not “contaminate” the proprietary code. Other aspects of license compliance may have lacked behind. Indeed, where ever there is software, there is open source software (“OSS”). According to Boston Consulting Group, 99% of the Fortune 500 companies use OSS.1 Further, under the 2022 Open Source Report, 77% of the companies participating in the survey increased their use of OSS last year.2 This indicates that nowadays it is more unusual not to use OSS in software development, which of course makes sense, as a general ban against it would probably make the development process just inefficient. Nevertheless, despite the popularity of OSS, companies still – even more than 30 years after the release of one of the most popular open source licenses, the GPLv2 – are not always fully familiar of what types of requirements are linked to OSS, and how to comply cost effectively. However, this is about to change as the wave of compliance hits every corner of a company.

Namely, as the use of OSS increases along the compliance awareness, new tools are emerging to bridge the gap. For example, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration in the United States has introduced a Software Bill of Material3 (SBOM), which may be used when distributing products that include OSS and other third party software. SBOM is a formal record containing the details and supply chain relationships and dependencies of various components used in a product. The SBOM aims at providing transparency of the software components used in a product, in order to identify and avoid known vulnerabilities and quantifying and managing licenses, among others. While at the moment use of SBOMs is not mandatory, such requirements may be introduced in the future in commercial relations in the spirit of compliance.

To avoid IPR infringement, compliance is a must

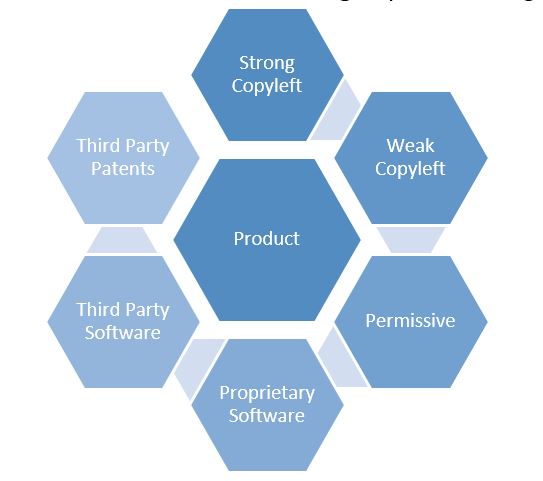

According to our view, there is even no need to talk about proprietary or open source, just (third party) code subject to various types of licenses. Irrespective of whether the question is of a commercial (expensive) standard software or a freely downloadable OSS available on the web, it is made available for use subject to a license. Whether the license is a proprietary or free/open source, it must be complied with. Period. Anything else means a breach of the license and hence, an infringement of third party intellectual property rights (IPRs). So far this is easy. How to achieve compliance in practise, may not always be.

“Whether the license is a proprietary or free/open source, it must be complied with. Period. Anything else means a breach of the license and hence, an infringement of third party intellectual property rights.”

OSS is released under licenses terms allowing free copying, modification and distribution of the code. However, OSS is not only provided ‘as is’, as few might think, but it is accompanied with a license that must be complied with when the OSS component is being distributed. In this context, “to distribute” means giving someone else a copy of the code, either in source code, or in binary code, or both. Therefore, it is imperative for the company using OSS in its software development to identify, analyse and comply with each license applicable to every single OSS component in the software architecture of the solution. A failure to comply with license requirements constitutes a breach of the license, and accordingly, the licensor’s intellectual property rights – always copyrights in the code, but possibly also the licensor’s patent(s) implemented by the software. Thus, one cannot simply use an OSS component and ignore the license. We see problems in license compliance postpone or even cancel deals, technology transactions and commercialization of solutions, if those intellectual property infringements are not fixed before closing or other consummation of the contract.

When it comes to OSS, the complexity comes from the magnitude of the code base, possibly millions lines of code, hundreds of different OSS components, subject to multiple different OSS licenses and various types of license conditions that may not even be mutually compatible in software architecture. The way to effectively manage the compliance process is automation. Use of OSS compliance tools based on carefully crafted algorithms following a conservative industry standard to operational compliance, is legal tech at its best. It removes the need for excessive manual labour by tech lawyers, hence saving the time for more complex cases requiring “handmade” compliance, for example in tricky technology transactions in M&A context, or other critical use cases.

Conservative industry standard to ensure OSS compliance

Consequently, it is in the company’s best interests to identify, analyse and comply with each license applicable to each OSS component used in the company’s business. In general, license conditions may include, for example, an obligation to provide the copyright notice and the license text in the documentation accompanied with the code to the recipient, e.g., to a customer. OSS licenses may be categorized to different types based on their criticality and source code distribution requirements, such as permissive, weak copyleft and strong copyleft licenses, depending on related “risks” meaning that permissive is the most liberal license with the least requirements while strong copyleft license is the most restrictive one. In case of back end software that is not distributed, there is less to worry, as in the absence of distribution, the license conditions are usually not triggered. However, even in cloud context there is sometimes distribution of code to customers, such as in case of private platforms, or due to some very (!) strong copyleft license, the APGL, which may have viral effect even over the air.

Permissive OSS licenses place limited restrictions on how the OSS component may be used and mainly include documentation requirements. In addition to the permissive licenses’ requirements of including copyright notice and license text in the documentation, other OSS licenses may also provide for a copyleft clause, which requires the user to distribute or offer to distribute the source code of the OSS component and any modifications to it, which jointly constitute a “derivative work”. A derivative work is a copyright related concept, which includes the combination of the OSS component and its additions or modifications. Thus, a copyleft clause may require that modifications to the OSS component must be re-licensed under the same license terms as the original OSS component, such as the GPL. This concept is called “viral effect”.

If a viral effect is triggered under a copyleft license, the company distributing the OSS component may be required to disclose its own proprietary code modifications and/or combinations and further provide the recipient with the right to copy, modify and distribute said code under the respective copyleft license for free. Therefore, the viral effect may put the company’s own IPRs at risk if required to disclose its own proprietary source code. Consequently, not being aware of the relevant license requirements might result in the company “accidentally” relicensing its proprietary copyrights and/or patents on one hand, or breach of third party IPRs on the other hand. And in worst case, the both.

However, it is worth noting that there are differences between copyleft licenses, as some licenses require that the source code must be provided for the whole derivative work (strong copyleft), and other licenses require only that source code is provided only on code file level (weak copyleft). The source code distribution requirement of weak copyleft licenses is less sweeping, i.e., more narrow compared to that included in the strong copyleft licenses. This is because the viral effect under weak copyleft licenses is limited only to the OSS component and does not spread beyond, which makes it possible to add, link or combine other software components to the weak copyleft licensed code without being “contaminated” by the viral effect.

It should also be noted that certain OSS licenses might be incompatible in a way that makes it impossible to utilize the OSS components in the same product, as the license conditions may conflict with each other to a degree that makes it impossible to comply with the conflicting terms simultaneously. However, utilizing OSS components with different licenses is not a problem as long as the terms and conditions of the licenses are compatible. In general, permissive licenses are compatible with each other and OSS components subject to weak copyleft licenses are usually compatible with each other. However, strong copyleft licenses are mainly only compatible with permissive OSS licenses. License compatibility review is an essential part of compliance.

Implementation of OSS strategy streamlines the compliance process

We recommend companies to prepare and implement an OSS policy or strategy so that it is customized to the company’s own R&D processes and then educate the relevant R&D personnel about the policy. An OSS policy governs the use of OSS and aims to maximize the impact and benefit of using OSS. It is a practical tool, to be followed in the software development process by the OSS responsible persons (not only lawyers) in order to ensure compliance with OSS licenses, maintain license compatibility in software architecture and secure the company’s own IPRs in its proprietary software, mitigate potential viral effects and even infringement of third party IPRs, both copyrights and patents. The idea is of course, to avoid manual labour and analysis of each use case by IPR & technology lawyers. It is critical that the OSS compliance process is carefully inbuilt into the company’s product creation process “by design” enabling a timely replacement of components and other changes in the software architecture in order not to delay the product creation process, especially in DevOps-style mode of operations.

In addition to the “outbound” scenario of distributing the company’s software solutions or contributing OSS code to the OSS community e.g. on GitHub, the OSS policy should also address the “inbound” sourcing aspects of, e.g., licensing and/or purchasing products for resale or incorporating third party software in the company’s products. This is because the OSS license requirements are triggered regardless of when and where the OSS is incorporated in the product. Therefore, a company using OSS either themselves or receiving software from its contracting parties, should always be aware of its actual content. The “outbound process” applicable to upstream code contributions makes sure that a company does not become negatively impacted by unwanted OSS license implications.

The use of OSS is increasingly growing and is a standard part of companies’ software development process. The nature of the OSS licensing model based on making available of content for free or subject to a reasonable price under standard terms is clearly something that is lucrative in the current markets. Interestingly, the EU Commission also aims to create a similar non-binding model of standard contractual clauses for sharing of industrial data under the proposed Data Act.4 Therefore, it is very intriguing to see how the open licensing model will be implemented in other technological areas and further, how the current OSS license model itself will adapt to the changes as well. Whether the question is of data or (OSS) code, related contract provisions concerning asset flows must be well crafted in all commercial contracts and in line with internal compliance guidelines, securing trade secrets in all assets by acknowledging the company’s internal interests while complying with both mandatory license and regulatory requirements. That is a sphere, which continues to keep our team busy also in the future, and where the new market standards are soon being shaped.

1“Why You Need an Open Source Software Strategywritten by Pranay Ahlawat, Johannes Boyne, Dominik Herz, Florian Schmieg, and Michael Stephan, 16.4.2021available at https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/open-source-software-strategy-benefits

2 “2022 Open Source Report Overview: Motivations for OSS Adoption” written by Javier Perez, 16.2.2022 available at https://javierperez.mozello.com/blog/params/post/3995889/2022-open-source-report-overview-motivations-for-oss-adoption

3Software Bill of Materials | National Telecommunications and Information Administration

4The new Data Act to lay foundation for a fair and innovative data economy – Dittmar & Indrenius